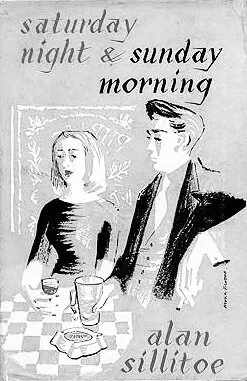

On Saturday Night and Sunday Morning

One of my lockdown projects is an attempt to watch the BFI’s 50 Greatest British Films. What I’ve realised is that whereas I thought I wasn’t a fan of classic film, I now suspect I just don’t much like classic American film. British cinema, however, feels like a powerful insight into the popular sensibility of a nation, in a way that the rarefied sphere of literature can never be. I asked my nonagenarian grandfather the other day if he went to the cinema much when he was a boy, and he replied ‘Oh, not really. Maybe twice a week.’

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning makes the past feel so close that you can almost smell the beer and cigarette smoke on its breath. People speak with a rhythm that still exists, without the twists and toffee-nosed vowels of 1950s RP. It is the story of Arthur, a young factory machinist. We meet him working, fitting a single part – a metal cylinder – and learn that he fits a thousand identical parts every day. Once we’ve seen him fit one, we’ve seen all thousand.

No surprise, then, that Arthur lives for the weekend. No surprise either that this film falls into the ‘angry young man’ trope. But this is a British, working class angry young man – no Marlon Brando in Taxi Driver. His ire against the world is largely manifest in throwing stones and shooting obnoxious neighbours with air guns. More boy than man.

We wonder about Arthur’s boyhood. The shadow of the war can still be felt – ‘Them were rotten days’, his Auntie Ada remarks. It’s strange to watch a story of British factory life that isn’t steeped in nostalgia; indeed, there’s an optimism in the sharpness of the suits that Arthur dons for his Friday and Saturday nights in the pub. That’s where he meets the gorgeous Doreen – a woman as finely-boned as Audrey Hepburn, if Audrey Hepburn had hailed from Nottingham. They make a gorgeous couple, and a life for them, together, seems possible. Doreen is aspirational – she wants a house ‘with a bathroom and everything’.

There’s a complication, because if there weren’t there wouldn’t be a film. Arthur is also carrying on with Brenda, the wife of an older colleague – and in due course he learns that she’s ‘in trouble’. I was struck by the openness of the conversation around this illegitimate pregnancy, from Brenda’s frank statement that she was ‘late’ to her reprimand of Arthur’s sloppiness with family-planning measures (‘you never take care’). There’s also a remarkable solidarity between Brenda and Auntie Ada when they discuss backstreet abortion (hot bath, gin. Doesn’t work.)

The beats of the film render it a little unconventional, perhaps a little uneasy, mirroring the rhythm of working life, of a working week, at the expense of narrative comfort. Ultimately, Brenda keeps the baby and raises it with her cuckholded husband, and Doreen and Arthur decide to marry. Perhaps Arthur is ambivalent about this plan – perhaps we all are, when we’re still young and angry.