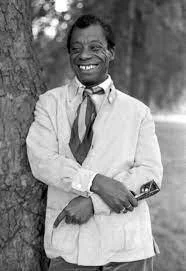

On Another Country

I haven’t read much James Baldwin, just If Beale Street Could Talk and, as of this weekend, Another Country. I picked up the latter about three years ago, and then put it down about a third of the way in. I couldn’t remember why, until I stumbled across this passage:

‘In that moment she knew, and she knew that Richard would never face it, that the book he had written to make money represented the absolute limit of his talent. It had not really been written to make money - if only it had been! It had been written because he was afraid, afraid of things dark, strange, dangerous, difficult and deep.’

What a frightening passage for a baby author to read, though now I’m inclined to frame it and hang it above my desk. Because the rewards of a writer exploring the dark, the strange, the dangerous, the difficult and the deep are that occasionally a genius like James Baldwin writes a novel like Another Country.

There are two writers in Another Country. There is Richard, who’s mediocrity is so agonisingly dissected above. And then there is Vivaldo, the white liberal who ‘tomcats around Harlem’ picking up prostituted African American women. Vivaldo, the Bohemian, who sits close to the centre of this dark, strange, difficult, deep book, but not at its heart.

For the heart of the novel is Rufus. A black man in New York, existing in uneasy relation to his surroundings: ‘The city has opened its doors to him, not enough for him to feel free, but just enough for him to feel danger and threat.’ We meet Rufus at his most precarious point, at near rock bottom, sleeping in the back row of a cinema and waking only to protect himself from robbery or molestation. A precarious man made more precarious by the surrounding world: ‘There were boys and girls drinking coffee at the drugstore counters who were held back from his condition by barriers as perishable as their dwindling cigarettes.’

What brought Rufus to this point? Being born black, is one answer. Another answer is the psychic rupture that occurs in him when he falls in love - or as close as two maimed souls can come to love - with a white Southern woman, Leona. Leona loves Rufus, but that doesn’t stop her from falling into the scripts of their respective births - her passing use of the word ‘boy’, for example, crackles with charge when she applies it to Rufus. And so he cannot love her, not entirely, not the way they might both want to. Yet they are drawn together:

‘He wanted her to remember him the longest day she lived. And, shortly, nothing could have stopped him, not the white God himself nor a lynch mob arriving on wings. Under his breath he cursed the milk-white bitch and groaned and rode his weapon between her thighs.... A moan and a curse tore through him while he beat her with all the strength he had and felt the venom shoot out of him, enough for a hundred black-white babies.’

A lot of this précis is just going to be me quoting Baldwin at length. I don’t think I’ve ever read better, more accurate renderings of the most searing moments of human experience. It makes you marvel that Baldwin is using the same English as the rest of us. He does something different with it. It is the Books of Revelations, it is poetry, it is ecstasy, it is terror. Here is Rufus on the subway platform, in the grip of one of those hideous psychic moments when the solidity of the world seems to dissolve and the underlying chaos reveals itself:

‘Suppose something, somewhere, failed, and the yellow lights went out and no one could see, any longer, the platform’s edge? Suppose these beams fell down? He saw the train in the tunnel, rushing under water, the motorman gone mad, gone blind, unable to decipher the lights, and the tracks gleaming and snarling senselessly upward for ever, the train never stopping and the people screaming at windows and turning on each other with all the accumulated fury of their blasphemed lives, everything gone out of them but murder, breaking limb from limb and splashing in blood, with joy - for the first time, joy, joy, after such a long sentence in chains, leaping out to astound the world, to astound the world again. Or, the train in the tunnel, the water outside, the power failing, the walls coming in, and the water not rising like a flood but breaking like a wave over the heads of these people, filling their crying mouths, filling their eyes, their hair, tearing away their clothes and discovering the secrecy which only the water, by now, could use. It could happen. It could happen; and he would have loved to see it happen, even if he perished too.’

Who can live for long in such a heightened consciousness? Not Rufus, burdened as he is with a psychic load that no human should have to shoulder, split by history between loving and hating, split by what DuBois called his ‘double consciousness’. It is less than a quarter of the way through the novel that we witness, with an intimacy that feels almost shameful, Rufus’ last moments:

‘He stood at the centre of the bridge and it was freezing cold. He raised his eyes to heaven. He thought, You bastard, you motherfucking bastard. Ain’t I your baby, too? He began to cry... He thought of Ida. He whispered, I’m sorry, Leona, and then the wind took him, he felt himself going over, head down, the wind, the stars, the lights, the water, all rolled together, all right. He felt a shoe fly off behind him, there was nothing around him, only the wind, all right, you motherfucking Godalmighty bastard, I’m coming to you.’

It is for Ida, Rufus’s ‘race-conscious’ sister, and Vivaldo, that white liberal writer friend, to understand the precise size and shape of the wound that Rufus has left behind, which they do through talk, through love, through sex (and sex, in Another Country be it between men and women or men and men, is shown to be both the site of profound wounds and a place of unrivalled freedom and possibility, as in the loving relationship between Eric and Yves) - through the scant and inadequate ways that any one human has of connecting with another. Connect they must, because they need each other in order to understand the nature of Rufus’ suffering, which was inextricable from the racism that he suffered:

‘But they didn’t... happen to you because you were white. They just happened. But what happens up here... happens because they are coloured. And that makes a difference.... You’ll be kissing a long time, my friend, before you kiss any of this away.’

But at the same time was larger than it, as large as the sum total of all humanity’s pain. Baldwin is not suggesting that anyone has a monopoly on pain, on the human condition:

‘When you’re older you’ll see, I think, that we all commit our crimes. The thing is not to lie about them - to try to understand what you have done, why you have done it... That way, you can begin to forgive yourself. That’s very important. If you don’t forgive yourself you’ll never be able to forgive anybody else and you’ll go on committing the same crimes for ever.’

Another Country is a novel about honesty and self-knowledge, even if it comes at a terrible price. He says, essentially, that the only person you ever kid is yourself (but, being Baldwin, he says it better):

‘The trouble with a secret life is that it is very frequently a secret from the person who lives it and not at all a secret from the people he encounters.’