On Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads, vol. 2

The true moral of Shirley Jackson’s short story ‘The Possibility of Evil’, is to beware of old ladies with a fondness for writing letters; they possess unplumbable depths of darkness in the hearts that beat beneath their chiffon blouses.

Imelda Staunton’s Irene is one such prim miss - the kind of woman who in modern times would write a one-star Yelp review for a crematorium - but since Talking Heads was written in the eighties, she contents herself with letters. Letters to MPs, letters to drug manufacturers, letters complaining that responses to letters are a waste of public resources.

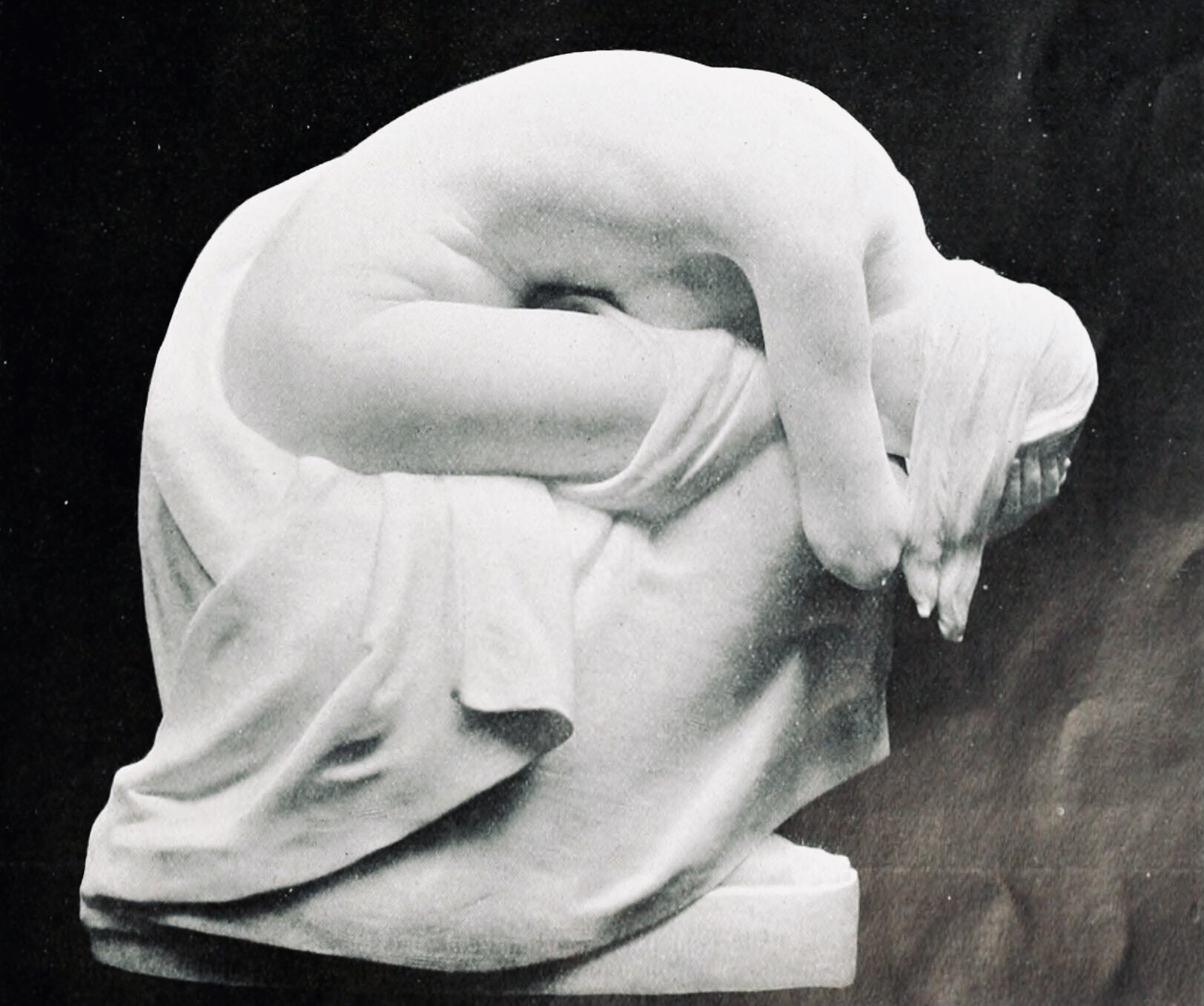

It’s as if Irene believes that if she can iron out the creases of the world then there is a - childlike - hope that she might keep evil at bay. But, like Jackson’s Adela Strangeworth - her attempts to repeal the darkness with her pen only create more of it.

Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads are about loneliness almost by definition - their subjects are the sort of people who will start talking just because they haven’t used their voice all day - they need to remember how it sounds. And it’s easy to understand, in lockdown, how life can shrink until a person is vacuum-packed in their tiny, airless world, where the only respite is to peer out at the neighbours and remark that the kiddie looks unwell, and that its lax, feckless parents don’t ever put down a tablecloth when they eat.

Irene is a dense, burning mass of rage and disappointment. She has no interest in other people except to criticise them. Because of her lack of knowledge of her fellow beings, she misunderstands things. She seems to care about the ‘kiddie’, but is the source of her care a desire to protect innocence or merely the relish of finding fault? We don’t know. I don’t think Irene does either. Staunton hints at both.

I won’t give away the ending, save to say that it’s masterful, and that Irene finds her joy in the end. She seems so natural in her happiness that we wonder whether it’s something that she’s rediscovered or found for the first time - if the latter, then she takes to it like a duck to water. Not because she’s fended off the darkness for good, but because she’s found a way to make a home there.