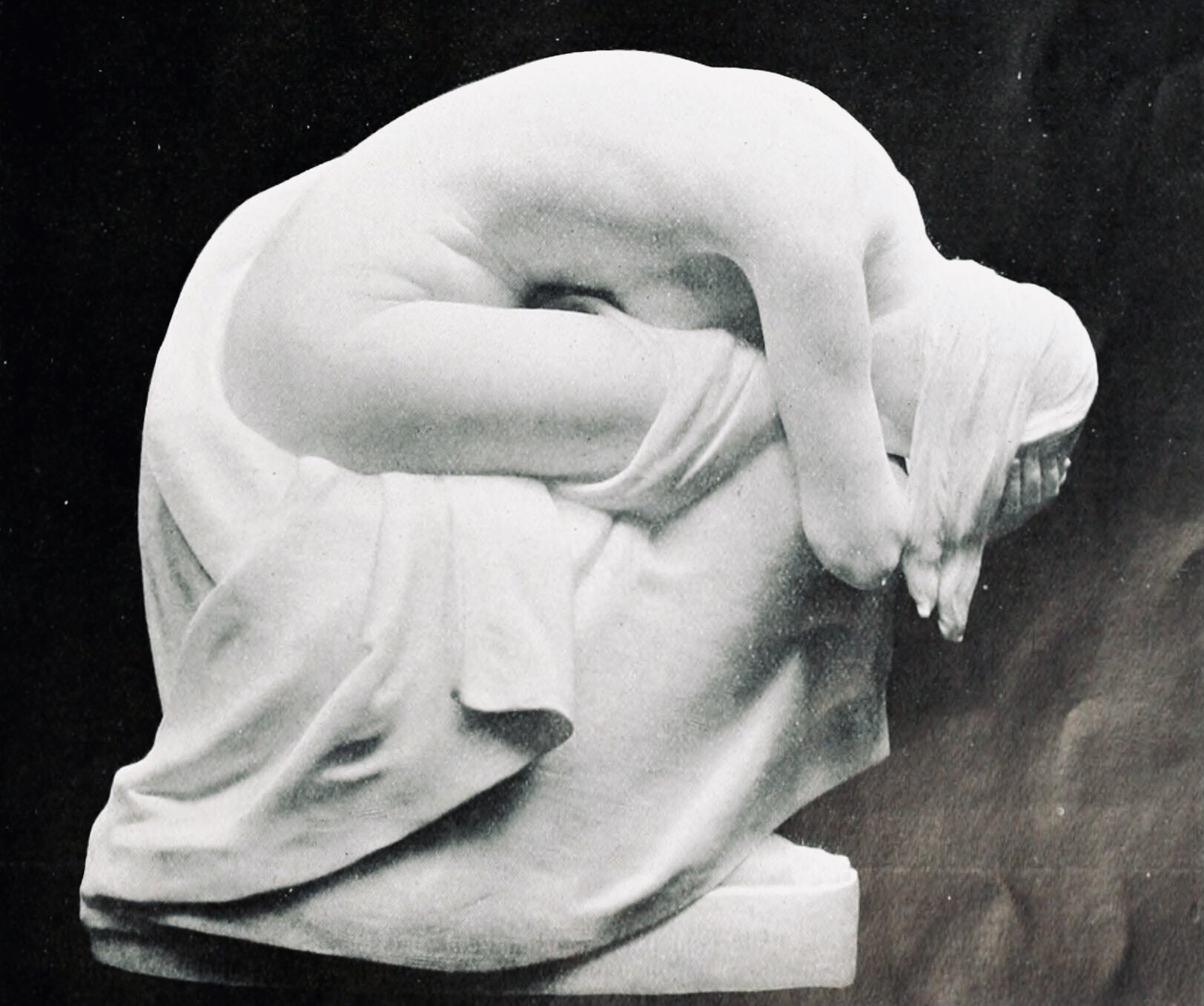

On ‘The Madness of Grief’

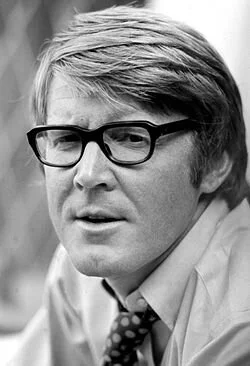

Richard Coles’ partner, David, died on December 13th 2019. Coles’ tweets, in the months that followed, convinced me that there is a value to Twitter - which I generally hate. The unfiltered observance of his grief, in real time, seemed a profound act of generosity - a gift born of sorrow and given to the world, in faith that some unknown person might need it. Coles said he wrote his memoir of David’s death, The Madness of Grief, because he had to. He writes:

‘In my experience, grief - my own and other people’s - does what it wants to do, it is not obedient to psychological patterning, or theological argument, or the opinion of anyone, least of all you. It comes when it comes, and it goes when it goes, and it can snatch you out of relative composure with unpredictable and irresistible force. And it is all yours, and no one else’s.’

The Madness of Grief is one of those pieces of art that is as miraculous for the fact of its execution as its content. How is it possible that he took that disorientation of those grief-stricken days and turned it so swiftly into a map, or at least a beacon?

Perhaps it is because Coles is more familiar with death than most. Priests have to be. He finds himself slipping into ‘vicar mode’ even at David’s deathbed. This familiarity is perhaps deepened by his experiences as a gay man in the 1980s, where he watched droves of men like him handed death sentences.

Perhaps it is because Coles seems so well-adjusted to the idea of death that the book feels like a distillation of pure loss, unhampered by the subsidiary hang ups that so many of us possess. Coles believes in eternal life, in some form. David, who was also a priest, goes to the grave equipped with the chancel that he will require as a tool of his trade when all mankind is resurrected. Nor does Coles appear to fear loneliness; he notes ‘we are not so much the author of our lives but a library of other people’. Throughout the book Coles is rarely alone, but always supported by a network of stalwart old friends. He positively enjoys his solo evenings on the sofa with one of the curries that David could not eat - but bereavement itself, the longing for David to come back. The most moving moment in the whole book, for me, saw Coles gently holding his love on the ICU bed, singing - not a hymn or a dirge - but Joni Mitchell’s A Case Of You.

‘The dead person persists most durably at the edge of things, in the unconscious habits which have accommodated them, impervious to the fact of their death.’

Coles lives with David’s handwriting on the jars of jam, searching for clothes that David borrowed and neglected to replace, doing his best to care for the five dachshunds that David acquired with profligacy.

And there’s the banality of loss: The parking situation at the hospital when Coles collects David’s death certificate. The desperate need to pee during the graveside ceremony. The car keys that David had last, and now Coles cannot find.

When I think about death, I think about Jeanette Winterson’s question: ‘Why is the measure of love loss?’ Reading The Madness of Grief feels like a privileged insight into a vast loss that measures, and honours, a love that was - and remains - just as vast.