On Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads

I’ve never seen Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads before. An oversight, I know. But the pleasure of that oversight is that I never realised what a monologue could be, until I learned today.

I learned this: that you discover the quality of a person’s isolation by the way they greet the possibility of an audience. That the best audience is one that asks, in its silences, the questions that the speaker longs to answer. That by indulging and giving attention to those answers, the speaker might admit things they never intended to reveal.

And that for every word spoken there are a thousand unsaid.

Kristin Scott Thomas is immaculate as Celia in The Hand of God. Those eyes - first wide with glee then dull and dimmed, implying a feeling of superiority that we discover to be unearned. Celia is an antiques dealer. She loves beautiful things. We infer that she has lost her husband, Laurence, and assume - from the tender quality of her silence, from the way those eyes flick to an unoccupied space - that she must have loved him.

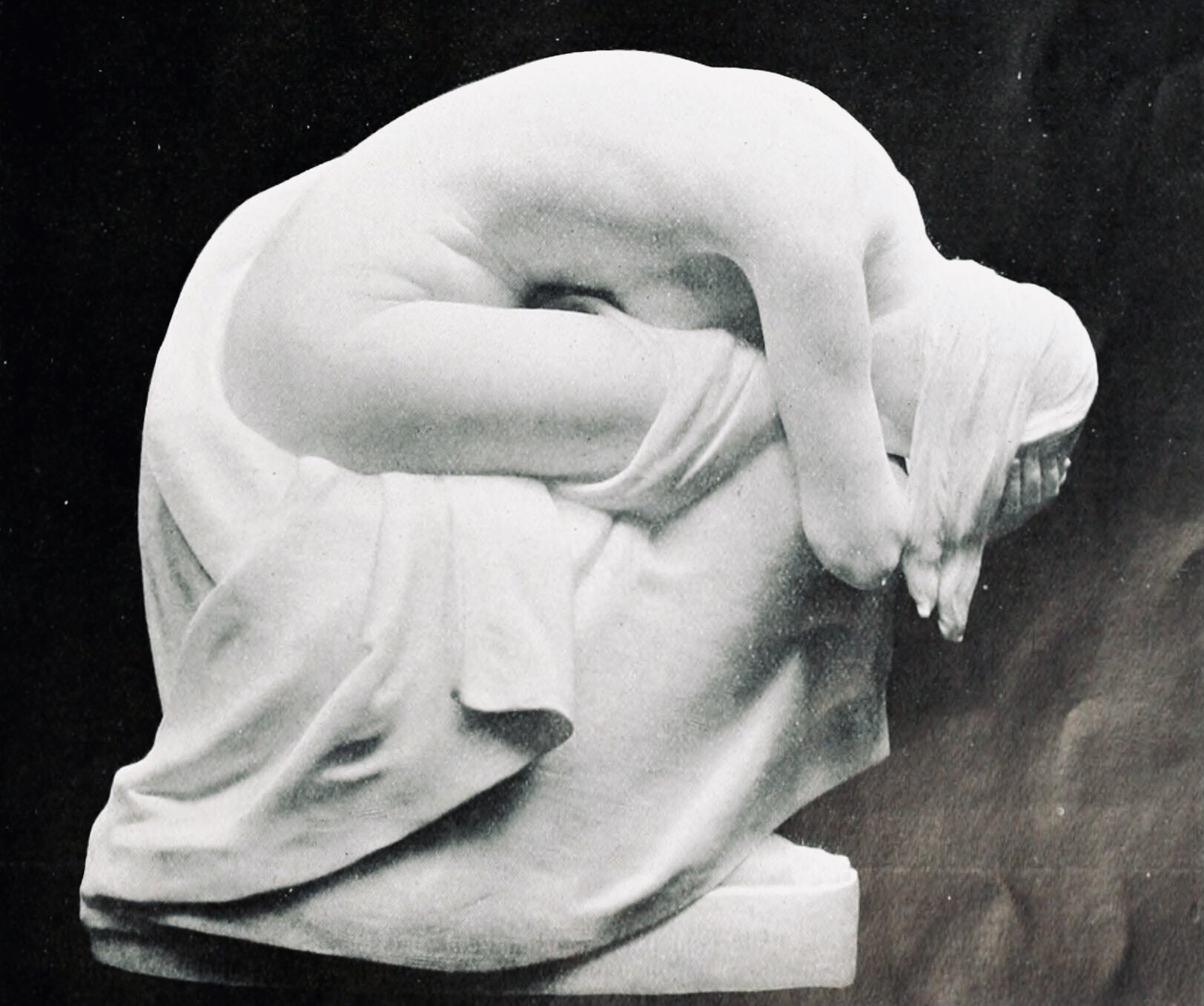

Yet now she’s doing things her way. Whereas he shifted stock at a clip, she will hold out. The right price for something that matters - and she knows what matters. She has - as she says with mingled pride and steel - ‘the eye’. Hers is a constant, semi-benign avarice, taking interest in a dying elderly neighbour only for the sake of her treasures. Things matter to Celia more than people, yet it is people that she claims to read best. She knows every trick in the book that a customer will try to pull on her.

Yet Celia finds herself undone - fleeced, the way she seeks to fleece - by a trick that she knew well. It’s a quiet humiliation. It tugs at a thread of who she is and we watch her whole being unravel. The only thing that comforts her is the thought that someone else has been cheated even more than she has. Her snobbery, her eagerness to win, is her undoing.

Yet we ache for Celia, sitting in her dark antiques shop. We ache because the bitchy asides and casual judgements sit alongside a pair of wide, defenceless eyes, the space where a husband once sat, and the voice of a woman speaking to no one.